Life is defined by our breath; it starts with the first one at birth, and ends with the last bit of air we take before we pass. Breathing is a bodily function we often take for granted, but if we think about it a little more closely it’s quite an incredible process. The average person breathes up to 28,000 times a day!

Breathing is the only function in our body that can be both autonomous (meaning it is prompted by our body without conscious thought) and conscious (for example we can decide to take deep breaths, or prompt our bodies to breath in and out quickly). When we stop to focus upon the breath, this small act can contribute to a healthier life in more ways than you think!

In this article we will explore the diaphragm, a part of our body that plays a very large role in breathing, and uncover how its health is vital to many other bodily functions. Here’s an introduction to the diaphragm’s amazing interconnectedness to other parts of the body:

What does the diaphragm really do?

Most people know that the diaphragm helps us breathe, that it’s somewhere in our chest, that it moves up and down, and that obnoxious health professionals, yogis, and people who meditate will tell you “you’re not breathing right.” If you’re left with little to no direction as to how to fix your breathing, or you simply don’t know how breathing works, it can make correcting it a difficult task.

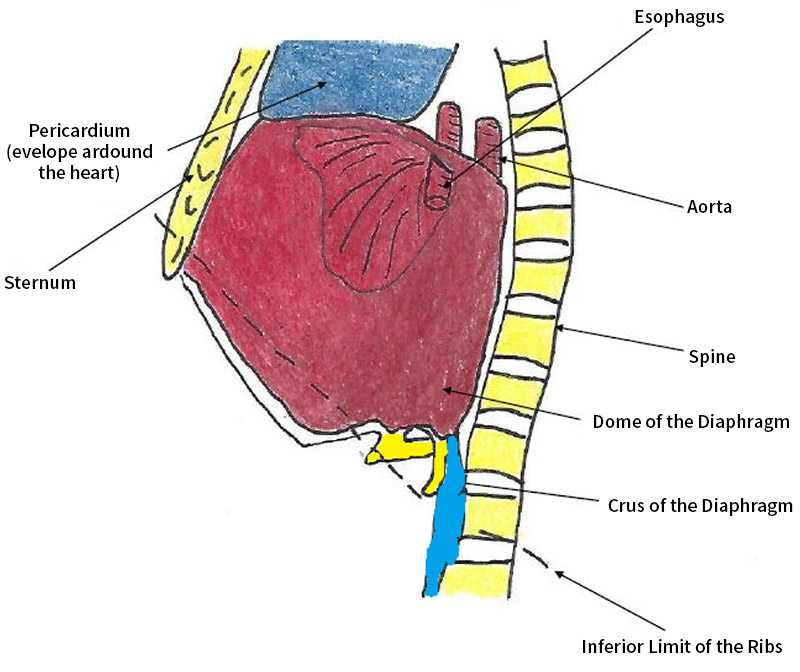

So, let’s take some time to explore some basic components of the diaphragm and how it relates to breathing (along with a few other functions in the body). The diaphragm has a very neat shape: it’s like a parachute in your chest. The outer attachment follows your lower ribs. The top of the diaphragm is shaped like a dome higher up in the chest; the right dome is slightly higher than the left, due to the volume of the liver on that side.

This diagram allows us to visualize the umbrella shape of the muscular dome of the diaphragm inside the chest.

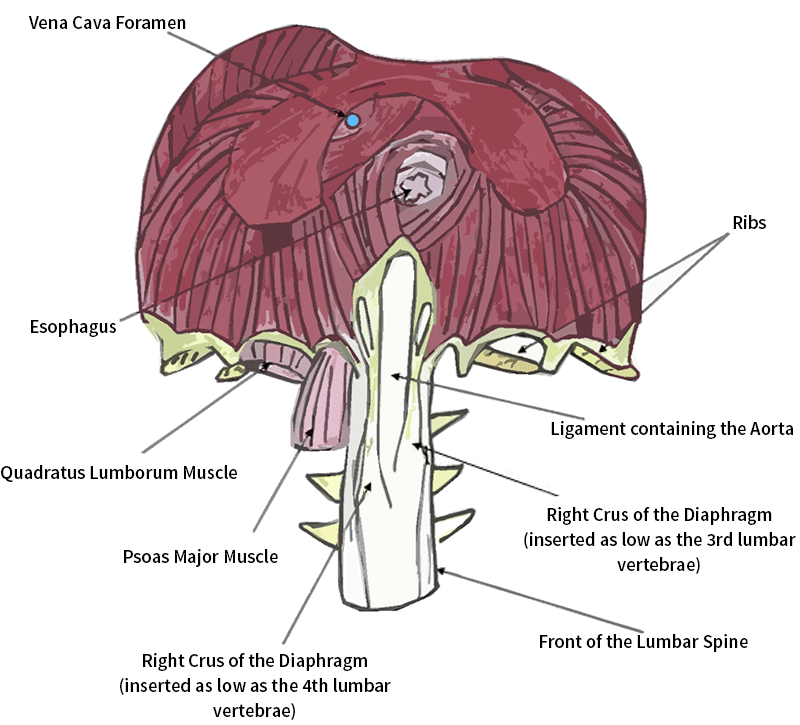

On the lower attachments of the diaphragm, pillar-like parts hold it in front of your lumbar spine. These pillars are called “crus.” We’ll explain later how the crus can contribute to lower back pain.

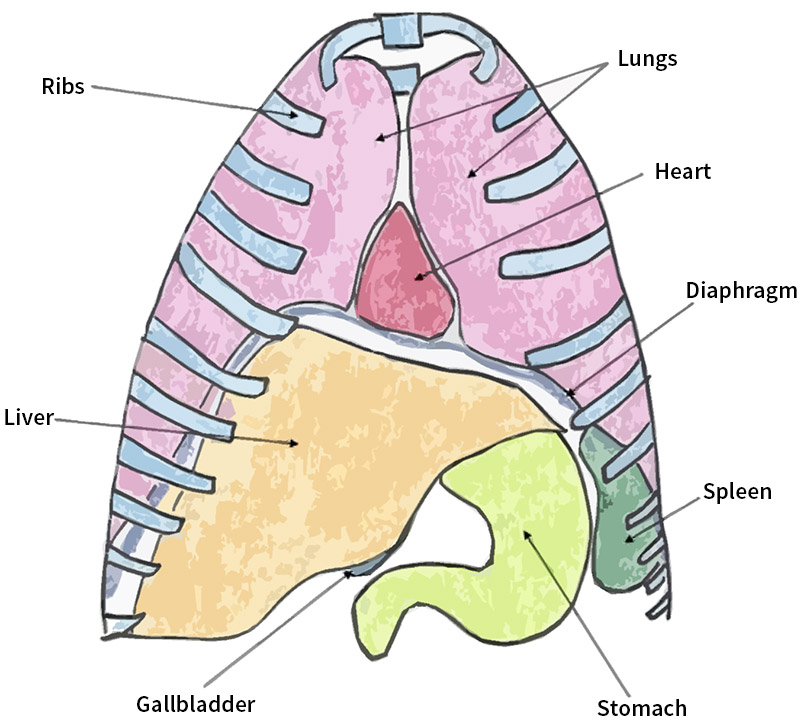

Let’s circle back to the dome shape part of the diagram we were just talking about! In this part there is a mass of muscle that has holes which the esophagus (a tube from the mouth to your stomach), the aorta, and some big veins and nerves (like the vagus nerves responsible for the brain-gut feedback) pass through. For osteopaths, the diaphragm’s direct connection to the lungs, heart, liver, stomach, spleen, and kidney are important to explore, especially when problems arise within these organs. Various rope-like ligaments link all of these together.

So, now that we know the structure of the diaphragm, let’s take a look at what it really does. The diaphragm is a great multi-tasker: it allows us to eliminate CO2 and waste through the lungs, it pressure regulates the chest, regulates blood vessels and the lymph, and with each movement, it gently activates the digestive tract underneath it. Thanks to its nerve connection to the autonomous nervous system, it can influence numerous systems like your heart beat or respiratory speed. It can also induce a state of relaxation, to name just a couple of its features!

Due to its vast influence around the body, the diaphragm’s dysfunction can be involved in many ailments including:

- chest pain

- a feeling of suffocation

- palpitations

- feeling bloated

- a poor forward posture

- poor blood flow to the legs

- problems with pelvic floor muscles

- ptosis (when organs drop lower than they should)

There can be multiple causes for these adverse symptoms, so let’s break them down for a better understanding.

This diagram helps us visualize the link between the diaphragm, lungs, heart, stomach, liver, and the spleen.

The diaphragm and your organs:

We have talked about the connection between the diaphragm and surrounding organs. Osteopaths will check the tonicity of the different parts of the diaphragm and examine the function of organs to find out how they have adapted in order to function to their best ability. This may be a little hard to follow, so let’s look at a few examples:

- A marathon runner will have great abs, but the repetitive impact of this sport will be hard on the suspensory system that holds organs, which can cause them to lengthen over time.

- A post-partum woman will experience a change of pressure in the abdomen which can create dysfunctions when the diaphragm moves down, and organs are restored to their “new” normal after the uterus has descended.

Both of these examples are more “mechanical” in nature. Another source of dysfunction can be found within nerves travelling through the diaphragm: the vagus and splanchnic nerves provide constant feedback from your guts to your brain and vice-versa. If one of these passes through a hypertonic (tight) diaphragm, their information transmission skills will be altered, causing digestive problems.

The diaphragm and blood flow

In a similar way, blood (in the arteries and veins) or lymph can be affected if a tension in the diaphragm does not allow their proper flow. The given problem may present itself with symptoms such as heavy legs or hemorrhoids. In fact, good breathing is a natural antioxidant which alkalizes the blood, lowering inflammation in the body!

The diaphragm, stress, and emotions

In a fight or flight state, our breathing accelerates, allowing us to run faster from a threat. Unfortunately, though our lives are often much safer than centuries ago, our bodies have not changed. As a result, small but frequent stresses can induce the fight or flight state. Everything from traffic jams to being late to an appointment, having an argument: all these stresses affect the diaphragm. Stressors like these can create a sensation of pressure, tightness in the chest, dizziness, poor digestion, shortness of breath, and so on.

If you were kneeling in front of someone (and were able to look through a few organs that cover the diaphragm), this is what you would see. This viewpoint allows us to better understand how lower back pain can be caused by dysfunction in the diaphragm in its lower position.

The diaphragm, your back, and ribs

There are different reasons why your diaphragm may induce back or rib pain. During a car accident, the seat belt puts pressure on your sternum (aka your “breast bone”). Often, we will hold our breath during this trauma, which causes further tension and pressure on our chest and spine. Any kind of emotional, physical, or chemical trauma affects how we breathe and can become problematic.

A day-to-day example of the diaphragm contributing to back pain can be related to our posture during work or hobbies. Some forward bending, twisting, or leaning to one side can cause problems when the diaphragm is restricted. Picking up your child after a long day might cause your back to seize up, as your diaphragm (which is attached on the front of your lumbar spine) was already pulling your spine forward too much.

“The 3 Diaphragms”

What? Three diaphragms?—but I thought there was only one? That’s right, but there is an osteopathic theory that views things a little differently.

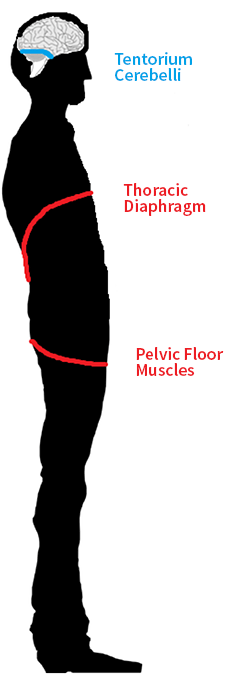

The theory argues that in order to regulate the pressure of the different “compartments” of the body, the body uses horizontal muscles and connective tissues to optimize both exchanges in the fluid systems and in pressure regulation. The body’s mass is separated into compartments and because it is composed of 80% water, the muscles and fascias move together, creating pump-like mechanisms to redistribute it.

The three prominent diaphragms in the Osteopathic community are:

- The Cranial Diaphragm, made of the tentorium cerebelli, a tent-like connective tissue separating the brain from the cerebellum, and that lets blood flow through.

- The Thoracic Diaphragm. You’ve got this one covered by now!

- The Pelvic Floor Muscles. The pelvic bowl is made out of bones, whereas its floor is composed of several muscles holding the pelvic organs. After a pregnancy, the pelvic floor becomes weak, causing organs to descend. In these cases, pelvic floor physiotherapists work on the proper contraction and relaxation of these muscles, and then pair that with breath work.

Other diaphragms in the neck and upper chest may also be considered by an osteopath. This theory of multiple diaphragms allows us to better understand a compensatory system of pressure between parts of the body that might otherwise seem unrelated.

So to wrap this up, our breath is like a good friend: always here for us, no matter what, and we always assume it’s there, doing its thing. But, sometimes it needs a little help. The diaphragm is an essential part of the body that does so much, and when we have this knowledge, it can help us understand why we may experience certain symptoms and what we can do to alleviate them. Whether it’s breathing exercises, working on the quality vs. the quantity of inhalation and exhalation, or stretching with chest openers, I hope that you are inspired to integrate a few new approaches into your daily life to give your diaphragm a little bit of support as it works to do so much!